UNEC Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences Volume 5, No 2, pages 17-26 (2025) Cite this article, 394 https://doi.org/10.61640/ujeas.2025.1202

Gas-Insulated Substations (GIS) play a critical role in high-voltage power transmission and distribution systems, particularly in densely populated urban areas and installations with space constraints, such as underground substations. Due to their compact design, high operational reliability, and enhanced safety features, GIS have emerged as a favorable alternative to conventional Air-Insulated Substations (AIS) [1-4]. The employment of sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆), a gas renowned for its exceptional dielectric and arc-quenching properties, enables GIS to operate effectively under high voltage conditions, significantly reducing the risk of electrical faults and equipment failures [5-7].

Despite these advantages, GIS systems are subject to certain technical challenges. A prominent concern is the presence of free conductive particles within gas-insulated compartments [8-9]. These conductive particles commonly result from the mechanical deterioration of internal components such as bolts, weld seams, and contact surfaces due to aging processes or recurrent mechanical stresses [10]. Additionally, improper handling during manufacturing, assembly, or gas-filling procedures can introduce foreign metallic debris into the enclosure [11]. The presence of these particles disrupts the uniformity of the electric field, creating localized field enhancements and thereby reducing the overall dielectric strength of the insulation system [12].

Under high electric field conditions, conductive particles can become mobilized and migrate toward regions experiencing elevated electrical stress. This dynamic behavior modifies the electric field distribution, increasing the probability of partial discharge (PD) occurrence [13-18]. Continuous exposure to PD significantly deteriorates the insulation materials, ultimately leading to dielectric breakdown [19, 20]. In severe scenarios, this deterioration can result in catastrophic equipment failures, causing unexpected outages and posing considerable risks to the stability and reliability of high-voltage power networks [21].

The objective of this research is to investigate the behavior of small conductive particles under various electric field conditions, with particular emphasis on particle interactions with insulating structures exhibiting specific geometrical features. The study aims to elucidate the roles of Coulombic and dielectrophoretic forces in particle movement, levitation, and trapping mechanisms. Insights obtained from this investigation are anticipated to facilitate the development of advanced design strategies and effective mitigation techniques, thereby reducing the adverse impacts of free conductive particles on GIS and enhancing the reliability and operational stability of high-voltage power systems.

2.1. Lorentz force law

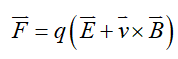

Electric and magnetic fields that vary with time are closely related and together influence the motion of charged particles. The total force (F) acting on a charge (q), which moves with velocity (v) in the presence of an electric field (E) and a magnetic field (B), is given by the Lorentz force:

(1)

(1)

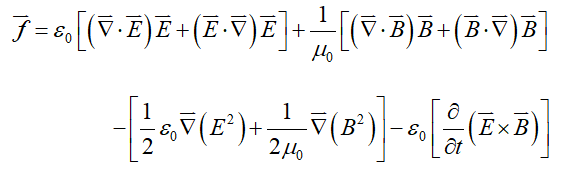

The force per unit volume, or force density, can also be derived from Maxwell's equations and is expressed as:

(2)

(2)

A clear understanding of particle behavior in gas-insulated substations (GIS) requires analyzing the forces that drive particle motion and their interaction with surrounding insulation materials. Conductive particles can acquire charge through mechanisms such as contact charging, field emission, or corona discharge, which then subjects them to motion governed by Coulomb forces in the electric field. Neutral or polarizable particles, on the other hand, experience dielectrophoretic (DEP) forces when exposed to non-uniform electric fields, leading them to migrate toward or away from regions of higher field intensity. Gravitational force further influences particle trajectories by affecting whether particles remain suspended within the gas or settle onto surfaces. In addition, friction force arising from interactions with the surrounding SF₆ gas slows particle motion, acting as a damping force that opposes movement and helps determine the steady-state distribution of particles within the enclosure.

The dielectric properties of the insulation system, such as permittivity, dielectric strength, loss tangent, and volume or surface resistivity play a crucial role in determining how particles interact with the electric field and accumulate charge. These properties directly impact the local field distribution, which can in turn alter the likelihood of particle movement and charging events. Uncontrolled movement or accumulation of conductive particles can initiate partial discharges (PD), degrading both the SF₆ gas and the solid insulation over time. Therefore, understanding the interplay between particle dynamics, electric field distribution, damping effects from friction, and the insulation material’s dielectric properties is essential for predicting and mitigating conditions that could lead to PD and ultimately compromise the reliability and lifespan of GIS equipment.

2.2. Maxwell stress tensor

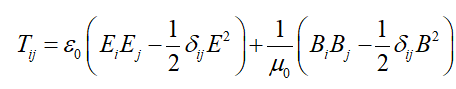

The force exerted by electric and magnetic fields on the surface of a particle is fundamentally governed by the Lorentz force, which represents the combined effects of electric and magnetic forces along each spatial axis. This relationship is expressed using tensor theory, resulting in a second-order tensor represented as a 3×3 matrix, where each component corresponds to the force acting in a particular direction.

(3)

(3)

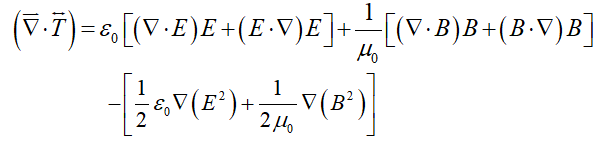

To express the force per unit volume in a tensor-consistent format, the scalar product between  and the Maxwell stress tensor

and the Maxwell stress tensor  is utilized to distribute the stress along each axis, as follows:

is utilized to distribute the stress along each axis, as follows:

(4)

(4)

Upon expanding the scalar product, equation 3 can be rearranged into the form of the Maxwell stress tensor as:

(5)

(5)

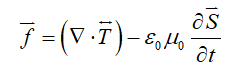

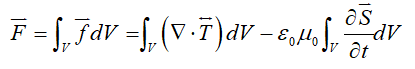

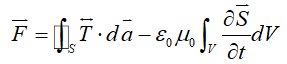

The total force acting per unit volume can be found as follows:

(6)

(6)

or

(7)

(7)

2.3 Particle dynamics, forces, and interaction with insulation systems

A comprehensive understanding of particle behaviour within GIS necessitates an in-depth analysis of the fundamental forces and charging mechanisms that influence particle motion. Conductive particles can acquire charge through processes such as contact charging, field emission, or corona discharge. Once charged, these particles are subjected to Coulombic forces acting within the electric field, driving their movement.

In addition to charged particles, neutral or polarizable particles are influenced by dielectrophoretic (DEP) forces when exposed to non-uniform electric fields. These DEP forces induce particle motion toward or away from regions of elevated field intensity—a behavior often characterized as a gradient force phenomenon—and can significantly affect particle distribution within the GIS enclosure. Gravitational forces further influence particle dynamics by determining whether particles remain suspended within the gas medium or settle onto solid surfaces, potentially forming localized contamination zones that increase electrical stress.

Beyond external forces, particle interactions with GIS insulation systems are significantly affected by the dielectric properties of materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and KAPTON. Characteristics such as dielectric constant, dielectric strength, loss tangent, and surface or volume resistivity govern the local electric field distribution and influence charge accumulation and retention on particles. Environmental factors—including temperature fluctuations, humidity, and long-term electrical stress—can alter these dielectric properties over time, potentially compromising insulation performance.

Uncontrolled particle movement and accumulation can trigger partial discharge (PD) events, which degrade both the SF₆ gas and solid insulation components. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms through which particles initiate PD, identifying the various PD types that may develop, and recognizing the breakdown conditions that could lead to insulation failure are essential steps in ensuring GIS reliability and prolonging system longevity.

To investigate the behavior, including the magnitude and direction, of the electrical force acting on a conductive particle under a high-voltage electric field, a simulation model was developed to closely replicate the experimental conditions. The setup consists of a high-voltage (HV) electrode positioned as the top plate, which can be inclined at various angles, and two distinct configurations of a grounded electrode serving as the bottom plate. A DC high-voltage potential is applied to the top electrode to generate a non-uniform electric field across the electrode gap. The study focuses on comparing particle responses under two different grounding conditions:

Configuration 1 Conductive Particle on Grounded Electrode:

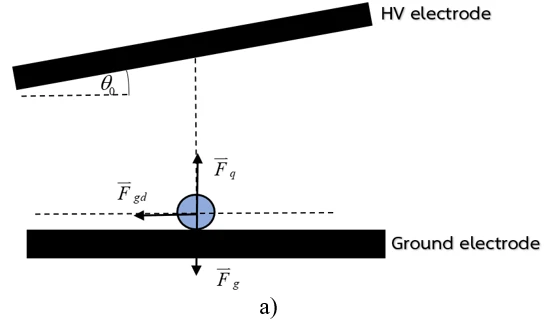

In the first case, a spherical aluminum particle is placed directly on the grounded electrode. The high-voltage electrode above is inclined at a specified angle relative to the horizontal plane. This inclination creates a gradient in the electric field distribution, which influences the electrostatic force acting on the particle. The minimum distance between the two electrodes is fixed for all simulations to maintain consistency. The initial position of the particle is measured from the edge of the grounded electrode. The schematic of this configuration is shown in figure 1. The relevant simulation parameters are listed in table 1.

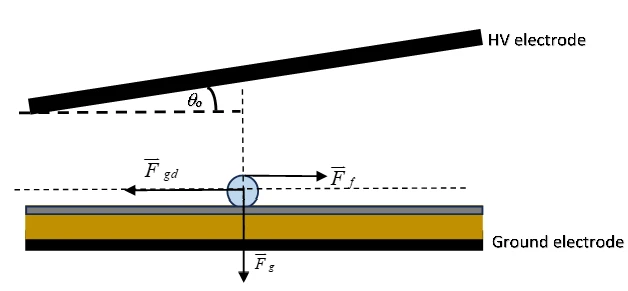

Configuration 2: Conductive Particle on Dielectric Surface

In the second configuration, two types of dielectric materials, KAPTON and PDMS, are layered and placed between the aluminum particle and the grounded electrode. The particle is positioned on the dielectric stack at the same initial location as in configuration 1. The presence of dielectric materials modifies the electric field distribution and influences both the magnitude of electric force and particle mobility due to surface insulation effects. A schematic representation of this configuration is shown in figure 2, and relevant parameters are listed in table 2.

This simulation framework allows for a systematic evaluation of electrical forces and resulting particle behavior under varying surface and voltage conditions. By comparing scenarios with and without dielectric layers, the model provides important insights into how surface material properties, electric field distributions, and electrode geometries collectively affect particle dynamics. These findings have direct implications for improving the design and insulation reliability of high-voltage equipment, particularly in operational environments where contamination by metallic particles presents a significant risk.

The simulation study revealed that variations in electrode configuration and dielectric layering significantly influence the motion of conductive particles. These factors alter both the magnitude and direction of the forces acting on the particles. The outcomes and analyses for two primary cases are presented below.

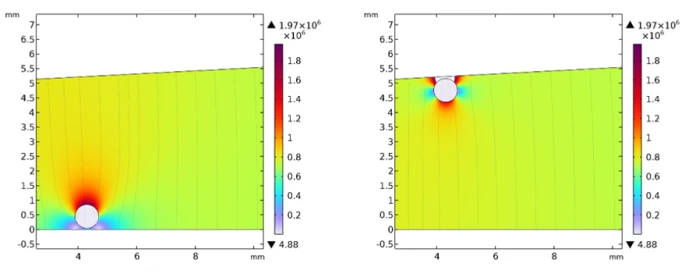

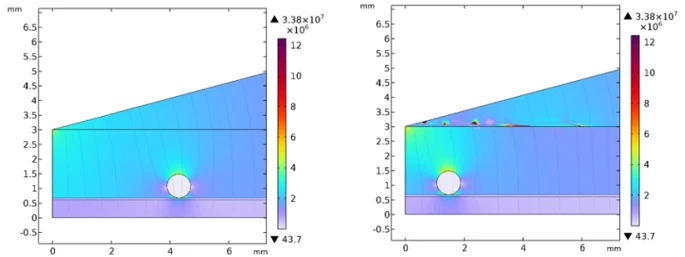

4.1 Conductive particle on grounded electrode

In this configuration, a spherical aluminum particle was placed directly on the grounded electrode. The simulation was conducted with the following conditions: initial particle position x = 4.3 mm, minimum electrode gap d =5 mm, electrode inclination angle θ =3∘, and applied voltage V = 4 kV. The results, shown in figure 3, illustrate the particle’s upward trajectory from the grounded surface to the high-voltage electrode. Initially, charge transfer mechanisms, such as contact charging, caused negative charges to accumulate on the particle’s surface, leading to an upward-directed Coulomb force. The inclined electrode geometry also created a gradient in the electric field, which produced an additional force component driving the particle toward regions of higher field intensity. Once the net electrical force exceeded the gravitational force, the particle lifted off from the grounded surface and accelerated toward the high-voltage electrode.

Upon contact, the particle acquired positive charge, leading to a reversal in the Coulomb force direction, now acting downward. This charge reversal and force switching behavior are presented in figure 4. These findings demonstrate the dynamic instability of free conductive particles in GIS environments and their potential to contribute to surface charging, field distortion, and partial discharge (PD) initiation.

Figure 3. Trajectory of a conductive particle placed on the grounded electrode. a) initial particle position electrode, b) particle in contact with upper high-voltage electrode

Figure 4. Electrostatic forces acting on a conductive particle placed on the grounded electrode. a) forces acting while the particle is on the ground

4.2 Conductive particle placed on a dielectric surface

To assess the impact of dielectric insulation, a two-layer dielectric surface (KAPTON and PDMS) was introduced between the particle and the grounded electrode. The simulation parameters were: initial particle position x = 4.3 mm, minimum electrode gap d =3 mm, electrode inclination angle θ =15∘, and applied voltage V =7.2 kV. Unlike the previous case, no charge transfer occurred at the interface due to the insulating layer, and thus no Coulomb force was induced to lift the particle. Instead, particle motion was governed by the axial component of the electric field gradient and the surface friction force. Once the gradient force exceeded the frictional resistance, the particle began to slide along the dielectric surface toward the region of higher electric field strength, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5. Particle behavior on a two-layer dielectric surface a) initial position of the particle, b) particle moves toward a region of stronger electric field

The force interactions acting on the particle in this configuration, including gradient force, gravity, and friction, are illustrated in figure 6. This lateral migration, though less dramatic than vertical lift-off, remains a concern in GIS, particularly near field-concentrating geometries or dielectric interfaces.

Figure 6. Electrostatic and frictional forces acting on a conductive particle on a two-layer dielectric surface

To quantify the effect of electrode geometry, simulations were performed at inclination angles of θ =3∘, 10∘, and 15∘. The results, shown in figure 7, reveal a clear relationship between inclination angle and the magnitude of the axial electric field gradient force. Larger angles resulted in steeper field gradients, which in turn enhanced the driving force on the particle along the dielectric surface. This behavior highlights the sensitivity of particle dynamics to geometrical design. Even in the absence of lift-off, conductive particles can be mobilized toward critical regions of the insulation system where local field enhancement may initiate discharge activity.

The simulation results provide critical insights into the electro-mechanical behavior of conductive particles under non-uniform electric fields, particularly in the context of gas-insulated systems. Two distinct scenarios were analyzed: a particle placed directly on a grounded electrode, and a particle situated on a composite dielectric surface comprising KAPTON and PDMS. The findings reveal that the interaction between the electric field distribution, electrode geometry, and surface material properties plays a pivotal role in determining particle motion and potential insulation threats.

In the configuration where the particle was in direct contact with the grounded electrode, surface charge accumulation occurred due to the transfer of electrical charge, resulting in an upward Coulomb force. When the magnitude of this force exceeded that of gravity, the particle detached from the electrode surface and accelerated toward the high-voltage electrode. Upon collision, the particle underwent charge reversal, acquiring positive charge and thereby reversing the direction of the Coulomb force. This cyclic behavior, involving lift-off and charge exchange, has significant implications for partial discharge activity and insulation degradation in GIS. The simulation quantitatively confirmed that electrode inclination contributes directly to electric field asymmetry, enhancing the electrostatic lift and increasing the likelihood of such destabilizing particle motion. In contrast, when the particle was positioned on an insulating surface, the absence of initial charge transfer suppressed the Coulomb lift-off mechanism. However, the particle remained subject to dielectrophoretic force arising from the spatial non-uniformity of the electric field. The simulation demonstrated that, once the field gradient force exceeded the surface frictional resistance, the particle initiated lateral migration along the dielectric interface. This motion occurred in the direction of increasing field intensity and became more pronounced at higher electrode inclination angles. The results underscore a less frequently discussed, yet critical risk in GIS environments: particle migration across insulation surfaces, which can still lead to localized field enhancement and discharge activity even in the absence of lift-off.

The study further highlighted the influence of electrode inclination angle on particle behavior. As the angle increased, the asymmetry of the electric field distribution was amplified, leading to a higher magnitude of axial gradient force. This force facilitated both lift-off (in the conductive case) and lateral drift (in the insulated case). These observations emphasize the importance of field geometry in determining particle stability and suggest that improper inclination or poor field uniformity may inadvertently promote particle motion and insulation stress. Overall, the results contribute to a broader understanding of how mobile conductive contaminants behave in gas-insulated environments, reinforcing the need for geometric and material considerations in the design of high-voltage insulation systems.

This study examined the dynamics of conductive particles exposed to high-voltage, non-uniform electric fields using numerical simulations of two practical scenarios: direct contact with a grounded electrode and placement atop a dielectric layer. The analysis demonstrated that when particles are directly in electrical contact with the grounded electrode, they gain charge through transfer processes, leading to Coulomb-driven lift-off and active motion toward the opposing electrode. Such particle movement can distort the local electric field, thereby increasing the likelihood of partial discharges or even flashover events. In contrast, when a dielectric surface separates the particle from the ground, vertical motion due to Coulomb force is largely suppressed. Nevertheless, particles still exhibit lateral movement driven by electric field gradients. The extent of this horizontal migration was found to depend strongly on the inclination angle of the high-voltage electrode, highlighting how geometric asymmetry can amplify particle instability.

The simulation results confirm that both vertical lift-off and lateral drift of conductive particles can compromise the dielectric reliability of gas-insulated systems. These effects are shaped by a combination of electric field intensity, electrode geometry, and surface characteristics of insulating materials. The findings emphasize the importance of thoughtful electrode design and insulation strategies in high-voltage equipment to reduce particle-related risks. Future research should prioritize experimental validation of these simulated behaviors under different environmental conditions and material aging scenarios. Additionally, investigating mitigation measures—such as modifying surface properties, applying dielectric coatings, or optimizing electrode shapes—could further improve the durability and reliability of insulation systems in real-world applications.

1 P. Rozga, A. Kraslawski, A. Klarecki, A. Romanowski, W. Krysiak, IEEE Access 9 (2021) 73413. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3080090

2 M. D'Souza, R.S. Dhara, R.C. Bouyer, IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 56(5) (2020) 4662. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2020.3006463

3 S. Okabe, N. Hayakawa, H. Murase, H. Hama, H. Okubo, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 13(2) (2006) 327. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2006.1624277

4 L.G. Christophorou, J.K. Olthoff, R.J. Van Brunt, IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 13(5) (1997) 20. https://doi.org/10.1109/57.620514

5 N. Dorraki, K. Niayesh, IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 37(6) (2022) 4646. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2022.3153237

6 H. Hofmann, C. Weindl, M.I. Al-Amayreh, O. Nilsson, IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 40(8) (2012) 2028. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2012.2200697

7 J.D. Mantilla, N. Gariboldi, S. Grob, M. Claessens, IEEE Electr. Insul. Conf. (2014) 469. https://doi.org/10.1109/EIC.2014.6869432

8 G.A. Hussain, W. Hassan, F. Mahmood, M. Shafiq, H. Rehman, J.A. Kay, IEEE Access 11 (2023) 51382. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3279355

9 X. Li, C. Cao, S. Zhang, J. Chen, Z. Sun, Y. Qiu, IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 38(6) (2023) 4039. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2023.3300835

10 X. Li, C. Cao, X. Lin, IEEE Access 10 (2022) 17212. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3150482

11 M. Mughal, A. Majid, F. Khan, U. Ahmad, W. Ullah, IEEE Access 10 (2022) 77239. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3192549

12 B. Qi, C. Li, Z. Xing, Z. Wei, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 21(2) (2014) 766. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2013.003585

13 P. Wenger, M. Beltle, S. Tenbohlen, U. Riechert, G. Behrmann, IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 34(4) (2019) 1540. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2019.2909830

14 H.-x. Ji, Y. Li, H. Li, D.-j. Song, J.-x. Yu, X.-b. Li, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 23(6) (2016) 3355. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2016.005881

15 B. Du, Z. Jin, J. Jiang, H. Liang, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 31(4) (2024) 2120. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2024.3368353

16 S. Okabe, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 14(1) (2007) 46. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2007.302871

17 J. Sun, L. Sun, W. Chen, Z. Li, X. Yan, Y. Xu, High Voltage 4(2) (2019) 138. https://doi.org/10.1049/hve.2018.5018

18 U. Schichler, W. Koltunowicz, S. Tenbohlen, U. Riechert, W. Holaus, J.-R. Riba, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 20(6) (2013) 2165. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2013.6678866

19 Y. Gao, Z. Li, H. Wang, X. Yuan, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 27(3) (2020) 998. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2019.008634

20 D.-E.A. Mansour, K. Nishizawa, H. Kojima, N. Hayakawa, F. Endo, H. Okubo, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 17(1) (2010) 247. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2010.5412024

21 A. Vinogradov, A. Vinogradova, V. Bolshev, CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 6(3) (2020) 537. https://doi.org/10.17775/CSEEJPES.2019.01920

N. Tanthanuch, Th. Anuraktrakool, N. Uchaipichat, Electrostatic behavior of conductive particles on conductive and dielectric surfaces in gas-insulated substation environments , UNEC J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 5(2) (2025) 17-26. https://doi.org/10.61640/ujeas.2025.1202

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ( CC BY 4.0 ) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

P. Rozga, A. Kraslawski, A. Klarecki, A. Romanowski, W. Krysiak, IEEE Access 9 (2021) 73413. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3080090

M. D'Souza, R.S. Dhara, R.C. Bouyer, IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 56(5) (2020) 4662. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2020.3006463

S. Okabe, N. Hayakawa, H. Murase, H. Hama, H. Okubo, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 13(2) (2006) 327. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2006.1624277

L.G. Christophorou, J.K. Olthoff, R.J. Van Brunt, IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 13(5) (1997) 20. https://doi.org/10.1109/57.620514

N. Dorraki, K. Niayesh, IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 37(6) (2022) 4646. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2022.3153237

H. Hofmann, C. Weindl, M.I. Al-Amayreh, O. Nilsson, IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 40(8) (2012) 2028. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2012.2200697

J.D. Mantilla, N. Gariboldi, S. Grob, M. Claessens, IEEE Electr. Insul. Conf. (2014) 469. https://doi.org/10.1109/EIC.2014.6869432

G.A. Hussain, W. Hassan, F. Mahmood, M. Shafiq, H. Rehman, J.A. Kay, IEEE Access 11 (2023) 51382. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3279355

X. Li, C. Cao, S. Zhang, J. Chen, Z. Sun, Y. Qiu, IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 38(6) (2023) 4039. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2023.3300835

X. Li, C. Cao, X. Lin, IEEE Access 10 (2022) 17212. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3150482

M. Mughal, A. Majid, F. Khan, U. Ahmad, W. Ullah, IEEE Access 10 (2022) 77239. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3192549

B. Qi, C. Li, Z. Xing, Z. Wei, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 21(2) (2014) 766. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2013.003585

P. Wenger, M. Beltle, S. Tenbohlen, U. Riechert, G. Behrmann, IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 34(4) (2019) 1540. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2019.2909830

H.-x. Ji, Y. Li, H. Li, D.-j. Song, J.-x. Yu, X.-b. Li, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 23(6) (2016) 3355. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2016.005881

B. Du, Z. Jin, J. Jiang, H. Liang, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 31(4) (2024) 2120. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2024.3368353

S. Okabe, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 14(1) (2007) 46. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2007.302871

J. Sun, L. Sun, W. Chen, Z. Li, X. Yan, Y. Xu, High Voltage 4(2) (2019) 138. https://doi.org/10.1049/hve.2018.5018

U. Schichler, W. Koltunowicz, S. Tenbohlen, U. Riechert, W. Holaus, J.-R. Riba, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 20(6) (2013) 2165. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2013.6678866

Y. Gao, Z. Li, H. Wang, X. Yuan, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 27(3) (2020) 998. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2019.008634

D.-E.A. Mansour, K. Nishizawa, H. Kojima, N. Hayakawa, F. Endo, H. Okubo, IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 17(1) (2010) 247. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2010.5412024

A. Vinogradov, A. Vinogradova, V. Bolshev, CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 6(3) (2020) 537. https://doi.org/10.17775/CSEEJPES.2019.01920