UNEC Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences Volume 5, No 2, pages 134-142 (2025) Cite this article, 170 https://doi.org/10.61640/ujeas.2025.1213

In this study, the biodegradation of brominated aromatic hydrocarbons by bacterial strains isolated from the coastal waters and soils of the Caspian Sea was investigated. As a result, 44 bacterial strains belonging to 10 genera were isolated, and it was determined that strains of the genus Pseudomonas were the most active in degrading brominated aromatic hydrocarbons. To further study the biodegradation process, a microbial consortium consisting of five active Pseudomonas strains was developed. This consortium of hydrocarbon-oxidizing microorganisms exhibited the highest degradation efficiency, completely metabolizing brominated aromatic compounds at concentrations of 50–100 mg/L. The degradation pathways were identified using HPLC, IR, and NMR spectroscopy, revealing mechanisms such as hydroxylation, side-chain oxidation, debromination, and ring cleavage. The degradation products were predominantly phenolic compounds, hydroxybenzoic acids, and bromobenzoic acids.

In addition to the fundamental results obtained, the collected data may form the basis of a methodological framework for future practical applications in the field of environmental biotechnology. The developed microbial consortium can be applied in the design of bioreactors and biofiltration systems for the treatment of industrial wastewater, as well as in the bioremediation of contaminated coastal areas of the Caspian Sea.

Bromine-containing aromatic hydrocarbons represent one of the most hazardous categories of pollutants, widely used in industry and agriculture as pesticides [1-3]. Upon entering aquatic ecosystems, these substances exert toxic effects on hydrobionts [4-6], disrupting ecosystem functions and reducing biodiversity in water bodies [7]. The issue of bromine-containing compound pollution is particularly critical in enclosed water bodies such as the Caspian Sea, which is subjected to intense anthropogenic impact, including discharges of petroleum products and chemicals [8]. As is well known, the Caspian Sea is among the most heavily polluted bodies of water in general [9]. In addition to oil, the sea receives vast amounts of other, equally hazardous pollutants and xenobiotics [10,11]. In recent decades, there has been growing interest in the use of microorganisms for bioremediation—natural processes of cleaning contaminated environments using bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms [12-15]. These microorganisms participate in the decomposition of a wide range of organic compounds, making them essential for maintaining ecological balance and redistributing nutrients in ecosystems [16,17]. They break down oil components, converting them into simpler and less toxic molecules, thereby helping to reduce environmental pollution levels [18,19]. Bacteria are highly effective in decomposing most pollutants, particularly those present in liquid or gaseous forms, such as hydrocarbons and oils. In particular, bacteria of the Pseudomonas genus are known for their ability to efficiently biodegrade various organic pollutants, including aromatic hydrocarbons and their halogenated derivatives [20]. Pseudomonas putida is capable of aerobic biodegradation of numerous organic compounds, including chlorinated aromatic compounds such as 1,1,1-trichloroethane, 1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane, trichloromethane, and tetrachloromethane [21].

Previously, we reported on the study of bacteria capable of utilizing phenols and chlorine-containing aromatic compounds as the sole source of carbon and energy [22]. However, for bromine-containing compounds, particularly bromine-containing aromatic hydrocarbons, data on natural degradation remain limited.

The aim of this study is to investigate the ability of bacteria, isolated from the waters and soils of coastal areas of the Caspian Sea in the Azerbaijani territory, to degrade bromine-containing aromatic hydrocarbons. This approach represents an important step in developing bioremediation methods for contaminated water bodies, as well as in understanding the ecological role of microorganisms in environmental cleanup processes. Thus, the study focuses on assessing the biodegradation of various bromine-containing aromatic hydrocarbons using bacteria isolated from specific ecosystems of the Caspian Sea.

The study was conducted on bacteria isolated from the coastal waters and soils of the Caspian Sea in the territory of Azerbaijan. The genus composition of the isolated bacteria was determined based on their morphological and physiological-biochemical characteristics according to Bergey’s Manual [23]. To investigate their ability to grow on media containing brominated aromatic compounds as the sole carbon source, the five most active Pseudomonas strains were utilized.

The dynamics of bromine-containing aromatic compound biodegradation by growing bacterial cells were studied in a medium with the following composition (g/L): Na₂HPO₄ – 0.7 g, KH₂PO₄ – 0.5 g, NH₄NO₃ – 0.75 g, MgSO₄ × 7H₂O – 0.2 g, MnSO₄ – 0.01 g, FeSO₄ – 0.02 g, NaCl – 13 g. The experiments were conducted in 250 mL flasks containing 100 mL of the nutrient medium. The tested compounds (para-bromophenol, tetrabromopyrocatechol, para-, meta-, ortho-bromotoluene, bromobenzene) were added to the flasks as the sole source of carbon and energy at concentrations of 50, 100, and 300 mg/L. Cultivation was carried out at 28ºC, and the intensity of the degradation process was assessed based on the biomass of microorganisms that developed on bromine-containing aromatic compounds over 45 days.

The structural transformations occurring during biodegradation of the studied aromatic compounds were analyzed using reversed-phase liquid chromatography. A “Kovo” (Czech Republic) liquid chromatograph was used, equipped with a UV spectrophotometric detector operating at a wavelength of λ = 254 nm. Two chromatographic columns (3.3 × 150 mm) filled with a reversed stationary phase “Separon SGX-C18” with a particle size of 7 µm were used. The temperature of the medium was maintained at 20–25ºC. The eluent consisted of a methanol-water mixture (75:25 vol.%), with a mobile phase flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. Component identification was performed by comparing the retention parameters of a standard mixture with those of the biotransformation products. Standard solutions with concentrations of 1–1.5 mg/mL were prepared in the elution system methanol-water (75:25 vol.%).

The structural composition of bromine-containing aromatic compound biodegradation products was determined using the following methods: IR spectroscopy (UR-20) (thin layer) in the spectral range of 4000–700 cm⁻¹; and ¹H NMR spectroscopy, performed on a “Tesla BS-487B” instrument with an operating frequency of 80 MHz in CCl₄, using hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDS) as an internal standard. Control experiments (without the addition of biodegrading bacteria) were conducted for all experiments.

A total of 44 bacterial strains were isolated from soil samples and coastal waters of the Caspian Sea within the territory of Azerbaijan and were identified as belonging to the genera Micrococcus, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Arthrobacter, Mycobacterium, Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Vibrio, Sarcina, and Alcaligenes. A consortium consisting of five more active Pseudomonas strains was developed, and its ability to biodegrade brominated aromatic hydrocarbons was investigated. The studied consortium was recorded to completely metabolize these compounds in test samples at concentrations of 50–100 mg/L. However, when the concentration of brominated aromatic compounds was increased to 300 mg/L, no degradation was observed during the monitoring period.

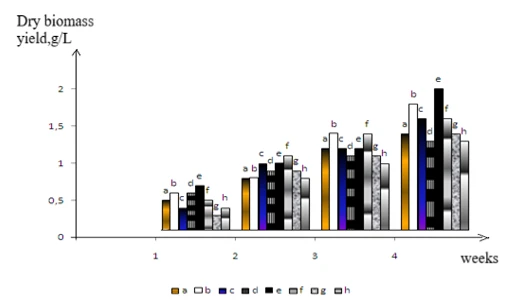

The accumulation of biomass in the medium supplemented with brominated aromatic compounds at a concentration of 100 mg/L is shown in figure 1. As observed in figure 1, when grown in this medium, the biomass of the strains in the consortium increased from 1.0 g/L to 1.8 g/L.

Figure 1. Biomass yield of the bacterial consortium when grown on brominated phenolic and aromatic compounds: a- ortho-bromophenol, b- para-bromophenol, c- meta-bromophenol, d- bromobenzene, e- tetrabromopyrocatechol, f- para-bromotoluene, meta-bromotoluene, ortho-bromotoluene

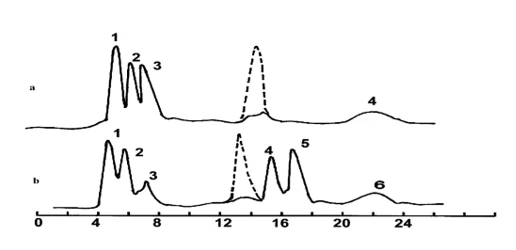

The degradation changes were studied using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). It was shown that the biotransformation process of bromine-containing aromatic hydrocarbons occurs similarly to the previously established identical degradation mechanism of benzene and toluene [8]. From the presented chromatogram in figure 2 (curve a), it can be seen that bromobenzene, during degradation, transforms into 4-bromopyrocatechol (32%), 5-bromopyrogallol (25%), para-bromophenol (25%) (peaks 1–3), as well as an oligomer (13%).

Figure 2. Chromatographic curves of bromobenzene biodegradation (a) and para-bromotoluene biodegradation (b). a-peaks: 1 – 4-bromopyrocatechol 2 – 5-bromopyrogallol 3 – para-bromophenol 4 – oligomer, b-peaks: 1 – 2,3-dihydroxy-p-bromobenzoic acid 2 – 4-bromosalicylic acid 3 – 2,3-dihydroxy-p-bromotoluene 4 – p-bromobenzoic acid 5 – 3-hydroxy-p-bromotoluene 6 – oligomer. Here and in the other figures, the original compounds are marked with dashed lines

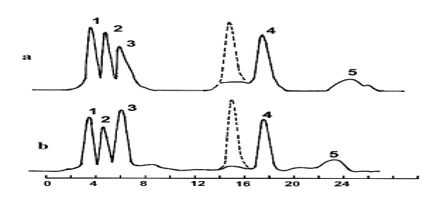

In the case of para-bromotoluene (curve b), as previously shown [22], the degradation mainly occurs through a mixed mechanism (oxidation of the side chain and the aromatic ring simultaneously) and leads to the formation of 2,3-dihydroxy-p-bromobenzoic acid (23%), 4-bromosalicylic acid (18%) (peaks 1 and 2), and p-bromobenzoic acid (18%) (peak 4). The degradation through oxidation of the aromatic ring is accompanied by the formation of 2,3-dihydroxy-p-bromotoluene (6%) and 3-hydroxy-p-bromotoluene (20%) (peaks 3 and 5). o-bromotoluene, when degraded by the mentioned bacteria (figure 3, curve a), transforms into 6-hydroxy-o-bromobenzoic acid (25%), 5-hydroxy-o-bromobenzoic acid (22%), and o-bromobenzoic acid (15%) (peaks 1-3), as well as 5-hydroxy-o-bromotoluene (20%) (peak 4) and oligomer (12%) (peak 5). In the case of meta-bromotoluene, 4-bromosalicylic acid (20%), m-bromobenzoic acid (18%), and 5-hydroxy-m-bromobenzoic acid (24%) were detected, along with 6-hydroxy-m-bromotoluene (22%) and oligomer (10%) (peaks 1-5).

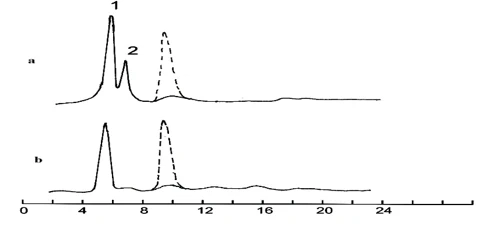

During the degradation of para-bromophenol, the products of its biotransformation were 4-bromopyrocatechin (58%) and 5-bromopyrogallol (36%) (figure 4, curve a) (peaks 1 and 2). It was established that the degradation of tetrabromopyrocatechin, similar to its chlorine-containing analog, occurs with the formation of tetrabromomuconic acid (curve b).

Figure 3. Chromatographic curves of biodegradation of ortho-bromotoluene (a) and meta-bromotoluene (b). a-peaks: 1- 6-hydroxy-o-bromobenzoic acid, 2- 5-hydroxy-o-bromobenzoic acid, 3- o-bromobenzoic acid, 4- 5-hydroxy-o-bromotoluene, 5- oligomer. b-peaks: 1- 4-bromosalicylic acid, 2- m-bromobenzoic acid, 3- 5-hydroxy-m-bromobenzoic acid, 4- 6-hydroxy-m-bromotoluene, 5- oligomer

Figure 4. Chromatographic curves of biodegradation of bromophenol (a) and tetrabromopyrocatechin (b). a-peaks: 1- 4-bromopyrocatechin, 2- 5-bromopyrogallol, b-peaks: tetrabromomuconic acid

The fastest degradation was observed in the case of para-bromophenol and tetrabromopyrocatechin (figure 3). In the case of para-bromophenol, the main products of its biotransformation were 4-bromopyrocatechin (15%) and 2,3-dihydroxy-m-parabromophenol (25%) (curve a), while in the case of tetrabromopyrocatechin, there was only one compound—tetrabromomuconic acid (curve b). It was established that, in these cases, the degradation of the studied compounds, unlike the previous ones, occurs simultaneously with debromination and the rupture of the phenolic ring.

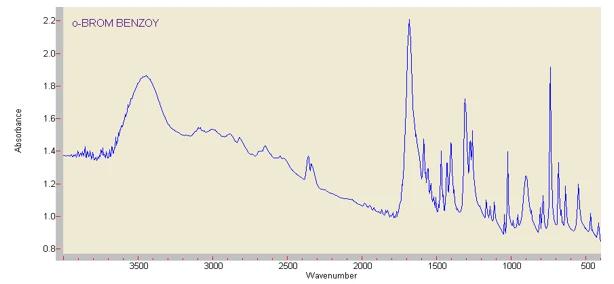

Figure 5. IR spectra of ortho-, meta-, and para-bromobenzoic acids obtained after biodegradation of brominated aromatic hydrocarbons. o – ortho-bromobenzoic acid

In addition to chromatographic analysis, the structure of the degradation products of bromine-containing aromatic compounds was also analyzed based on the data from IR (infrared) and NMR (proton magnetic resonance) spectra. The structures of the degradation products of brominated aromatic compounds were confirmed using IR and NMR spectroscopy. IR spectra (figure 5) show characteristic bands for the aromatic ring (1600–1640 and 3030–3045 cm⁻¹), C–Br bonds (600–700 cm⁻¹), and carboxyl groups (1710–1735 and 3450–3600 cm⁻¹). Figure 5 presents the IR spectra of ortho-, meta-, and para-bromobenzoic acids formed as intermediates. Para-bromobenzoic acid is formed via oxidation of the methyl group of p-bromotoluene followed by hydroxylation of the aromatic ring, as confirmed by chromatographic and IR data (figure 2b). NMR spectra further support the presence of aromatic, hydroxyl, and carboxyl protons, confirming the cleavage of C–Br bonds and effective detoxification by the Pseudomonas-based consortium.”

In the IR spectra (figure 5), absorption bands at 1600-1640 and 3030-3045 cm⁻¹ indicate the presence of an aromatic ring. Bands at 600-700 cm⁻¹ are characteristic of the C-Br bond. The presence of absorption bands in the region of 1710-1735 cm⁻¹ (C=O) and 3450-3600 cm⁻¹ (O-H) indicates the presence of a carboxyl group [24].

The bands at 1600–1640 and 3030–3045 cm⁻¹ indicate the presence of the aromatic ring, while the bands at 600–700 cm⁻¹ correspond to the C–Br bond. The absorption bands at 1710–1735 cm⁻¹ (C=O) and 3450–3600 cm⁻¹ (O–H) confirm the formation of carboxyl groups. The formation of para-bromobenzoic acid occurs via oxidation of the methyl group of p-bromotoluene followed by hydroxylation of the aromatic ring.

In the NMR spectra, chemical shift signals at 6.70-6.85; 7.50-7.70; 10.10-10.50 ppm are present, corresponding to the protons of the aromatic ring, hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, respectively.

The ecological impact of the identified intermediates, such as phenolic derivatives and brominated benzoic acids, was evaluated. Previous studies and our analyses showed that these compounds are neither persistent nor highly toxic and are further degraded by the microbial consortium into simpler and less toxic substances under aerobic conditions. IR and NMR analyses confirmed the disappearance of C–Br bonds and the cleavage of the aromatic ring. Thus, the developed Pseudomonas-based consortium effectively detoxifies not only brominated aromatic hydrocarbons but also their intermediate degradation products.

Based on the results of laboratory studies, it was determined that microbial consortia were able to significantly reduce the number of pollutants in both aquatic and soil environments.

The results obtained during the experiments confirm existing knowledge about the ability of microorganisms to break down complex organic pollutants such as brominated phenols and aromatic hydrocarbons. In this context, the data can be compared to similar studies focused on the biodegradation of aromatic hydrocarbons and their halogenated derivatives. One of the key studies in the field of brominated compound biodegradation is the research by [25], which examined the ability of various Pseudomonas strains to degrade chlorinated organic pollutants. The results of that study showed that Pseudomonas strains are capable of effectively degrading chlorinated hydrocarbons, such as chlorobenzene and its derivatives, through several stages of oxidation of both the aromatic ring and the side chain. It is important to note that although that study focused on chlorinated rather than brominated compounds, the mechanisms described are very similar to those observed in the present study, including the formation of intermediate products such as chlorosalicylic acid, which is analogous to the formation of bromosalicylic acid in our case.

The conducted studies by [26] also confirm the activity of Pseudomonas bacteria in the biodegradation of bromine-containing organic compounds, especially in the context of water pollution. These studies demonstrated that these bacteria can break down compounds such as bromophenols and bromotoluenes through hydroxylation and debromination processes, which are similar to those identified in the present study. Particularly interesting are the findings that during the biotransformation of brominated aromatic hydrocarbons, not only carboxylic products are formed, but also organic acids with hydroxyl groups, as observed in the degradation products of bromophenol in our study.

Moreover, the results of studies by [27-29] focused on the bioremediation of brominated compounds also highlight the importance of Pseudomonas strains in the removal of such pollutants. Their research demonstrated that under microbial activity, both debromination and structural modification of the aromatic ring occur, which is consistent with the findings of our study regarding various brominated phenolic and aromatic compounds.

By comparing data from various studies, it can be concluded that the biodegradation of brominated hydrocarbons is a complex process involving oxidation of the aromatic ring, hydroxylation, and, in some cases, cleavage of the aromatic ring. The advantage of Pseudomonas strains lies in their ability to adapt to diverse chemical structures of brominated pollutants and effectively transform them into less toxic compounds.

Thus, the current results complement and confirm the findings of other studies conducted in the field of biodegradation of brominated aromatic hydrocarbons. They highlight the importance of using microorganisms for the remediation of water bodies and soils contaminated with such substances and open new perspectives for further research in the field of bioremediation, especially involving Pseudomonas strains and other similar bacteria capable of effectively breaking down brominated organic pollutants.

The results of this study can be applied in engineering and environmental practice for the biological treatment of wastewater and the restoration of coastal zones. Microbial consortia can be incorporated into biofiltration or bioreactor systems to ensure the effective degradation of brominated aromatic hydrocarbons. The application of microbial consortia in soil and aquatic ecosystems can facilitate the remediation of contaminated areas. Furthermore, the development and testing of immobilized bacteria-based reactors hold promise for the treatment of industrial wastewater. By integrating biological processes with advanced oxidation and adsorption techniques, the efficient removal of more complex pollutant mixtures can be achieved.

In this study, bacterial strains isolated from the coastal waters and soils of the Caspian Sea demonstrated the ability to utilize bromine-containing aromatic compounds as a carbon source. Among the isolates, a Pseudomonas-based consortium exhibited the highest biodegradation efficiency, completely degrading brominated aromatic hydrocarbons at concentrations of 50–100 mg/L.

The findings confirm that these microorganisms are capable of transforming and detoxifying brominated aromatic compounds through oxidation, debromination, and ring cleavage processes. This highlights their strong potential for use in environmental biotechnology, particularly in the bioremediation of contaminated aquatic and soil environments.

Overall, the results contribute to the development of microbial technologies for cleaning industrial wastewater and restoring polluted coastal zones of the Caspian Sea, offering a sustainable and environmentally friendly solution for managing halogenated organic pollutants.

1 R. Jin, M. Zheng, G. Lammel, B.A.М Bandowe, G. Liu Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 76 (2020) 100803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2019.100803

2 P.K. Arora, H. Bae, Microbial Cell Factories 13 (2014) 31.

3 P.K. Arora, A. Srivastava, S.K. Garg, V.P. Singh, Bioresource Technology 250 (2018) 902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.12.007

4 D. Rebelo, S.C. Antunes, S. Rodrigues, Journal of Xenobiotics 13(4) (2023) 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox13040038

5 Z. Huang, C. Wang, G. Liu, L. Yang, X. Luo, Y. Liang, P. Wang, M. Zheng, Environmental Pollution 361 (2024) 124882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124882

6 S. Hajiyeva, T. Aliyeva, M. Yusifova, Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 192 (2020) 780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-08762-9

7 K. Kulzhanova, Z. Tekebayeva, A. Temirbekova, A. Bazarhankyzy, A. Temirkhanov, G. Bissenova, T. Mkilima, Z. Sarmurzina, Journal of Ecological Engineering 25(11) (2024) 55. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/192683

8 M.G. Veliev, M.A. Salmanov, A.A. Babashly, S.R. Alieva, N.R. Bektashi, Petroleum Chemistry 53(6) (2013) 426. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0965544113050101

9 M.A. Salmanov, Ecology and Biochemical Productivity of the Caspian Sea, Baku (1999) 400p.

10 E. Ramazanova, B. Yingkar, K. Yessenbayeva, S.H. Lee, W. Lee, Marine Pollution Bulletin 181 (2022) 113879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113879

11 M. Ahmadov, F. Humbatov, S. Mammadzada, V. Balayev, N. Ibadov, Q. Ibrahimov, Assessment of heavy metal pollution in coastal sediments of the western Caspian Sea volume 192(500) (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-08401-3

12 M.S. Ayilara, O.O. Babalola, Frontiers in Agronomy 5 (2023) 1183691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fagro.2023.1183691

13 G. Hasanova, A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, N. Gadimova, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 6(10) (2023) 35.

14 G. Hasanova, A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, Journal of Ecological Engineering 26(4) (2025) 323. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/200429

15 P. Pimviriyakul, T. Wongnate, R. Tinikul, P. Chaiyen, Microbial Biotechnology 13(1) (2019) 67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13488

16 V. Udod, I. Vildman, E. Zhukova, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 5(10) (2014) 4. https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2014.28003

17 M. Gerginova, G. Spankulova, T. Paunova-Krasteva, N. Peneva, S. Stoitsova, Z. Aleksiyeva, Fermentation 9(11) (2023) 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9110957

18 A.A. Krivushina, T.V. Bobyreva, E.V. Nikolaev, A.V. Slavin, Aviation Materials and Technologies 3(60) (2020) 66. https://doi.org/10.18577/2071-9140-2020-0-3-66-71

19 B.R. Chhetri, P. Silwal, P. Jyapu, Y. Maharjan, T. Lamsal, A. Basnet, International Journal of Applied Sciences and Biotechnology 10 (2022) 104. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijasbt.v10i2.44303

20 Sh. Sharma, H. Pathak, International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience 2(1) (2014) 213. https://www.ijpab.com/form/2014%20Volume%202,%20issue%201/IJPAB-2014-2-1-213-222.pdf

21 D. Popescu – Stegarus, C. Paladi, E. Lengyel, C. Tanase, C. Anamaria, V. Niculescu, Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Chemia 66(1) (2021) 143. https://doi.org/10.24193/subbchem.2021.01.11

22 A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, N. Gadimova, RT&A 17(70) (2022) 567. https://doi.org/10.24412/1932-2321-2022-470-567-572

23 P. De Vos, G.M. Garrity, J. Dorothy, N.R. Krieg, W. Ludwig, F.A. Rai, Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology 3 (2011) 1450. file:///C:/Users/ASUS/Downloads/bergeysmanualofsystematicbacteriology2009.pdf

24 A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, N. Gadimova, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 5(10) (2023) 125. https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2023.287467

25 Q. Lu, R.A. Toledo, F. Xie, J. Li, H. Shim, Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22(18) (2015) 14043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4644-y

26 N. Balaban, F. Gelman, A.A. Taylor, Sh.L. Walker, A. Bernstein, Z. Ronen, Applied Sciences 11(14) (2021) 6263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146263

27 F. Hu, P. Wang, Y. Li, J. Ling, Y. Ruan, J. Yu, L. Zhang, Environmental Research 239(1) (2023) 117211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.117211

28 J.A.C. Monzon, C.E.Q. Cerna, J.B. Saavedra, D. Valdivia, M. Esparza, Bioscience Research 18(2) (2022) 1294.

29 B. Muthukumar, M.S. Al Salhi, J. Narenkumar, S. Devanesan, T.N. Rao, W. Kim, A. Rajasekar, Environmental Pollution 304 (2022) 119223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119223

A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, B. Nas, R. Iqbal, M.T. Ismayilov, Biodegradation of brominated aromatic hydrocarbons using Pseudomonas bacteria isolated from water and soil of the coastal areas of the Caspian Sea in the territory of Azerbaijan , UNEC J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 5(2) (2025) 134-142. https://doi.org/10.61640/ujeas.2025.1213

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution ( CC BY 4.0 ) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

R. Jin, M. Zheng, G. Lammel, B.A.М Bandowe, G. Liu Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 76 (2020) 100803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2019.100803

P.K. Arora, H. Bae, Microbial Cell Factories 13 (2014) 31.

P.K. Arora, A. Srivastava, S.K. Garg, V.P. Singh, Bioresource Technology 250 (2018) 902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.12.007

D. Rebelo, S.C. Antunes, S. Rodrigues, Journal of Xenobiotics 13(4) (2023) 604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox13040038

Z. Huang, C. Wang, G. Liu, L. Yang, X. Luo, Y. Liang, P. Wang, M. Zheng, Environmental Pollution 361 (2024) 124882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124882

S. Hajiyeva, T. Aliyeva, M. Yusifova, Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 192 (2020) 780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-08762-9

K. Kulzhanova, Z. Tekebayeva, A. Temirbekova, A. Bazarhankyzy, A. Temirkhanov, G. Bissenova, T. Mkilima, Z. Sarmurzina, Journal of Ecological Engineering 25(11) (2024) 55. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/192683

M.G. Veliev, M.A. Salmanov, A.A. Babashly, S.R. Alieva, N.R. Bektashi, Petroleum Chemistry 53(6) (2013) 426. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0965544113050101

M.A. Salmanov, Ecology and Biochemical Productivity of the Caspian Sea, Baku (1999) 400p.

E. Ramazanova, B. Yingkar, K. Yessenbayeva, S.H. Lee, W. Lee, Marine Pollution Bulletin 181 (2022) 113879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113879

M. Ahmadov, F. Humbatov, S. Mammadzada, V. Balayev, N. Ibadov, Q. Ibrahimov, Assessment of heavy metal pollution in coastal sediments of the western Caspian Sea volume 192(500) (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-08401-3

M.S. Ayilara, O.O. Babalola, Frontiers in Agronomy 5 (2023) 1183691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fagro.2023.1183691

G. Hasanova, A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, N. Gadimova, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 6(10) (2023) 35.

G. Hasanova, A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, Journal of Ecological Engineering 26(4) (2025) 323. https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/200429

P. Pimviriyakul, T. Wongnate, R. Tinikul, P. Chaiyen, Microbial Biotechnology 13(1) (2019) 67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13488

V. Udod, I. Vildman, E. Zhukova, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 5(10) (2014) 4. https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2014.28003

M. Gerginova, G. Spankulova, T. Paunova-Krasteva, N. Peneva, S. Stoitsova, Z. Aleksiyeva, Fermentation 9(11) (2023) 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9110957

A.A. Krivushina, T.V. Bobyreva, E.V. Nikolaev, A.V. Slavin, Aviation Materials and Technologies 3(60) (2020) 66. https://doi.org/10.18577/2071-9140-2020-0-3-66-71

B.R. Chhetri, P. Silwal, P. Jyapu, Y. Maharjan, T. Lamsal, A. Basnet, International Journal of Applied Sciences and Biotechnology 10 (2022) 104. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijasbt.v10i2.44303

Sh. Sharma, H. Pathak, International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience 2(1) (2014) 213. https://www.ijpab.com/form/2014%20Volume%202,%20issue%201/IJPAB-2014-2-1-213-222.pdf

D. Popescu – Stegarus, C. Paladi, E. Lengyel, C. Tanase, C. Anamaria, V. Niculescu, Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Chemia 66(1) (2021) 143. https://doi.org/10.24193/subbchem.2021.01.11

A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, N. Gadimova, RT&A 17(70) (2022) 567. https://doi.org/10.24412/1932-2321-2022-470-567-572

P. De Vos, G.M. Garrity, J. Dorothy, N.R. Krieg, W. Ludwig, F.A. Rai, Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology 3 (2011) 1450. file:///C:/Users/ASUS/Downloads/bergeysmanualofsystematicbacteriology2009.pdf

A. Babashli, N. Akhundova, N. Gadimova, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 5(10) (2023) 125. https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2023.287467

Q. Lu, R.A. Toledo, F. Xie, J. Li, H. Shim, Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22(18) (2015) 14043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4644-y

N. Balaban, F. Gelman, A.A. Taylor, Sh.L. Walker, A. Bernstein, Z. Ronen, Applied Sciences 11(14) (2021) 6263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146263

F. Hu, P. Wang, Y. Li, J. Ling, Y. Ruan, J. Yu, L. Zhang, Environmental Research 239(1) (2023) 117211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.117211

J.A.C. Monzon, C.E.Q. Cerna, J.B. Saavedra, D. Valdivia, M. Esparza, Bioscience Research 18(2) (2022) 1294.

B. Muthukumar, M.S. Al Salhi, J. Narenkumar, S. Devanesan, T.N. Rao, W. Kim, A. Rajasekar, Environmental Pollution 304 (2022) 119223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119223